I got into technology early on, but not by my own choosing. It was in the Fall of 1978 at North Carolina State University. I was in my last semester of college, looking forward to teaching high school mathematics.

There were six of us graduating in December of that year. They called us together for an announcement that I did not appreciate at the time.

They said, “Someone is going to need to teach computer science, and we think it’s going to be math teachers.”

They then announced that they had added 2 credit hours to our graduation requirements (remember, we were just 4 months away from graduation), specifically requiring us to take a computer science course.

Punch cards. For the uninitiated, one card was like one line of code in today’s world. If you dropped your stack of cards, it was like shuffling the deck. Beyond the fun of using the little punched-out chads as confetti (and there were buckets of those), I did not enjoy that class. I barely passed.

And, just 3 weeks after graduation, I was teaching – wait for it – math and computer science at a local high school. There was no textbook. I had to study every night to create the course on the fly. But that’s when it all began to make sense to me.

After one and half years of teaching, I entered seminary (with an IBM Selectric typewriter) to prepare for youth ministry. While not an expert in any shape or form, in every church I served, I was still the one on staff that had a better technology clue than most.

When I returned to Seminary in the early 1990’s, one of my jobs was in the data center for Union Pacific Resources – entering data for their world wide oil wells holdings.

That’s when I first learned that there was a mismatch in what databases were for, and what most people thought databases were for.

Most people thought (and may still do) that databases were a place to store data. I found that, because no controls were available for manual data entry, there could easily have been, for example, dozens of misspellings of the name of a single well. Multiply that by typos for location, output, and any of the other 20 data points we entered, and all one could really say was that the database was doing a great job of storing data.

That’s not what a database is for. A database is most useful for what you can get out of it, rather than how much you can put in it. And what you can get out of it is directly tied to HOW you put it in.

Paul admonishes Timothy (and us) in 2 Timothy 2:15 to “… rightly handle the word of Truth.”

We should always be concerned with good doctrine and all principles of Biblical interpretation. Principles of Interpretation (original language, the meaning of words, culture, audience, etc.) and good doctrine are the data, and we don’t want any spiritual typos in our data, so these are certainly part of rightly handling God’s word.

But think with me for a moment of what you get out of that database, based on how you put the data in.

Lecture, commentaries, and vetted literature, for example, are the best ways to make sure of correctness of all the data points and doctrinal integrity for any passage of scripture. They also allow one to cover more territory, or less, depending on the volume of data you want to enter.

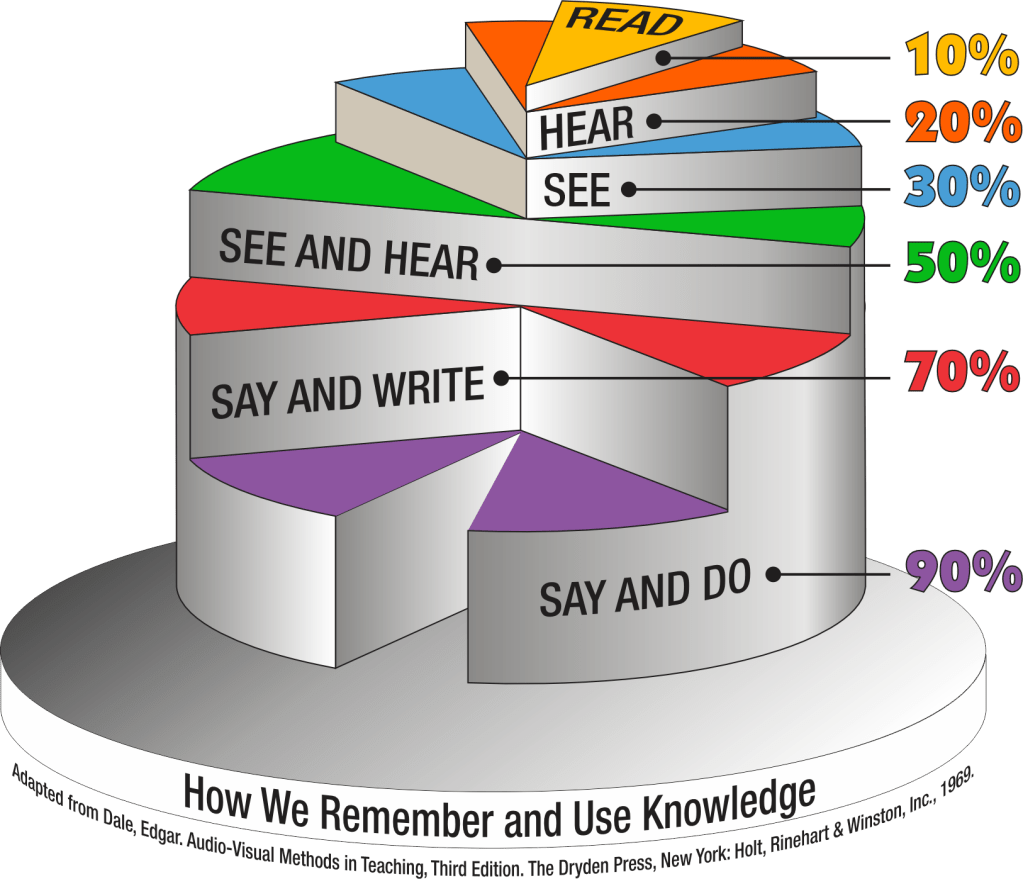

But every principle of education tells us that the average listener of the lecture input method will be able to get out no more than 20% of the data put in this way. Reading is even worse. The expected use of data entered via reading is about 10%.

This is not at all to say that reading and listening to sermons is not productive. Believers should read the Bible and the Gospel should be proclaimed every Sunday (and every other day of the week).

But, take this test if you dare. Walk around on Sunday morning before or after your service, and ask random people, “What did our pastor preach on last week?”

You may find that 20% easily remember without prompting, but most won’t. And that decreases over time. Ask them about 2 weeks ago. Ask them to tell you about the sermon that had the greatest impact on their life in the last year.

This is not bad. This should be expected. This is the way God made us to learn. This is normal. The proclamation of God’s word is very important. But if the members of your small group Bible study don’t do any better than 20%, perhaps you should consider how you’re presenting that data.

There are methods that are vastly more effective in getting data out. The best involve well-structured discussion (saying and writing is 70%, saying and doing is 90%). I say well-structured, because how you get the data in is very important to how it comes out.

One way to consider this is the weight lifter vs the juggler.

The weight lifter in the image is an academic student. There is the unstated expectation in this learning environment (Greek-style) that the participants will remember what the teacher/preacher says. If you want to know more, then study more and read more. Join a 2nd Bible study, or even a third. Gain as much Biblical knowledge as you can. Because Greek logic tells us that the more knowledge you possess, the more able you will be to live for Christ and stand against the enemy’s schemes.

Yet every statistic shows what you and I know. The church is in decline. Baptisms are down. Small group Bible study is a declining option among members of churches across the country. Is it possible they think they are carrying enough ‘weight’? Or perhaps they realize that 20% of what is coming out of their database isn’t life-changing for them?

Academic discipleship does not produce the results we think they should because academic discipleship is focused on getting data into the database, not on how it comes out.

The juggler, on the other hand, is also concerned about doctrine and principles of Biblical interpretation. But the data enters the juggler’s database through (Hebraic-style) connections, analysis, actions, and reactions. And these categories involve thoughtful conversation, not passive listening.

The juggler will actively remember what they did, days and weeks later, because they are engaged in the process of moving, managing, and in a sense, wrestling with that data. The interactive variety strengthens the juggler’s ability to juggle more concepts, see their connections and flow, and thereby handle God’s word more effectively.

The Solomon’s Quest framework can help your Bible study leaders move from putting data in to empowering those in their groups to engage with God’s word in a memorable, life-changing way. It is the same data found in reading and lecture, but the Solomon’s Quest framework enables facilitators to handle God’s word more effectively, creating the same ability in others. This is a critical missing step in many of today’s disciple-shaping offerings.

My son-in-law, a brilliant data warehouse developer, might tell you that a good database helps transform data into information.

We must empower God’s people toward the transformation of the renewed mind (Rom 12:2), giving them the ability and experience in transformed Biblical thinking about everything that might come their way. This strategy will produce all manner of sound Biblical information beyond what might be read or heard weekly.

The world does not challenge believers with the same Bible information that they study. The world doesn’t ask, for the most part, questions of believers that are being asked in formal Bible study groups.

The world challenges the lack of the renewed mind with questions like, “Why didn’t God…”, and “Why does God…”, and “Why doesn’t God…”.

If our disciple-shaping is filled with books, lectures, and videos about Biblical content, rather than learning to manage the manifold concepts of God’s word, these questions create stumbling blocks for the believer to stand (Ephesians 6). They can rack their brains for the passage that was studied or the verses they have memorized, and at a 20% rate, will struggle to be able to thoughtfully engage to the benefit of the questioner and the cause of Christ.

But if they have experienced critical thinking and analysis as part of the disciple-shaping, they are far better equipped to face a world that will find more ways to challenge believers than we might find ways to pour data into their brains.

A Real Life Real Time Example

Just this week, I engaged with an unbeliever on one of the social platforms on just such a question. An original post by someone else called out the magnificence of creation by describing a picture of a plant living in the depths of the ocean, with its crystal lattice framework giving it the strength to withstand the pressure at such depths.

The commenter asked (with the deliberate small ‘g’),

“if god had created this, why hide it at the bottom of the sea?”

There are a myriad possible answers, but what would your people say? I can imagine God-honoring responses, like:

- God can do what He wants

- God wants to continue to surprise us with His creation

- We can’t know everything that God has in mind

But answers like that are for the one that already has a faith in God that can be satisfied with the unknown.

Scripture has better answers for this kind of question, and one practiced in critical thinking can discover them in real time.

Not that this is the best or only response, but I knew this gentleman was not looking for Biblical truth – he was looking to challenge Biblical truth. “Hide” was the key word in the question. By the use of that word, he revealed his position on the importance of man, either by man’s own doing, or the mistaken position that God should have done all He did for us, rather than for Himself.

My response?

“Maybe because he created for His purpose, design, fulfillment, and enjoyment, not ours?”

He then challenged my use of the word “enjoyment”, saying “only a man born of woman would say god’s enjoyment. Is this the spirit of aegypt?”

This one question comprises multiple standard debate tactics that are easily identified with practice in Biblical thinking. He first challenged me with something true, in an accusatory tone, hoping to get me to defend myself against what sounded like a false accusation.

“Only a man born of a woman…” That’s true. I am a man born of a woman, regardless of how he posed the challenge.

He also tried to elevate his definition of ‘enjoyment’ without actually stating what it was. And then, as a third volley, he implied that I was following some other spiritual force. I had no need to be distracted by or to defend in that direction.

I responded:

“Well, He said it first in various ways and places ages before I was born (Gen 1:31, Psalm 104:31, Psalm 149:4, Pro 8:22-31, etc.). Mine is a simple ‘man born of woman’ paraphrase. It is certainly an error common to man to interpret words through personal filters rather than the meaning of the speaker. Thereby, the word “enjoyment” could mean all manner of things. Yet in this context, it means only what He means, not what you or I mean.”

Please know that I had no academic or ‘prepared’ knowledge of any of those verses. I had none of them memorized. What I had was the sure knowledge of the concepts of God’s purpose in creating and the why and how He has engaged with His creation. Knowing what I knew and where to find what aligned with what I knew, it was an easy matter to apply ample specific, irrefutable, Biblical evidence of my claim, while also identifying the distracting elements of the argument.

He concluded the thread with:

“I respect you and the strength of your conviction. Thank you for taking the time.”

We must prepare our people to stand for Christ in a world that would destroy them and/or their faith, rather than preparing them to perform well inside the walls of the church or at church ministry events outside the walls.

Granted, you won’t get as much data in every week as a lecture and/or homework readings, but those involved in a Quest study will, with certainty, get more out.

Follow Solomon’s Quest and reach out today to learn more.

Leave a comment